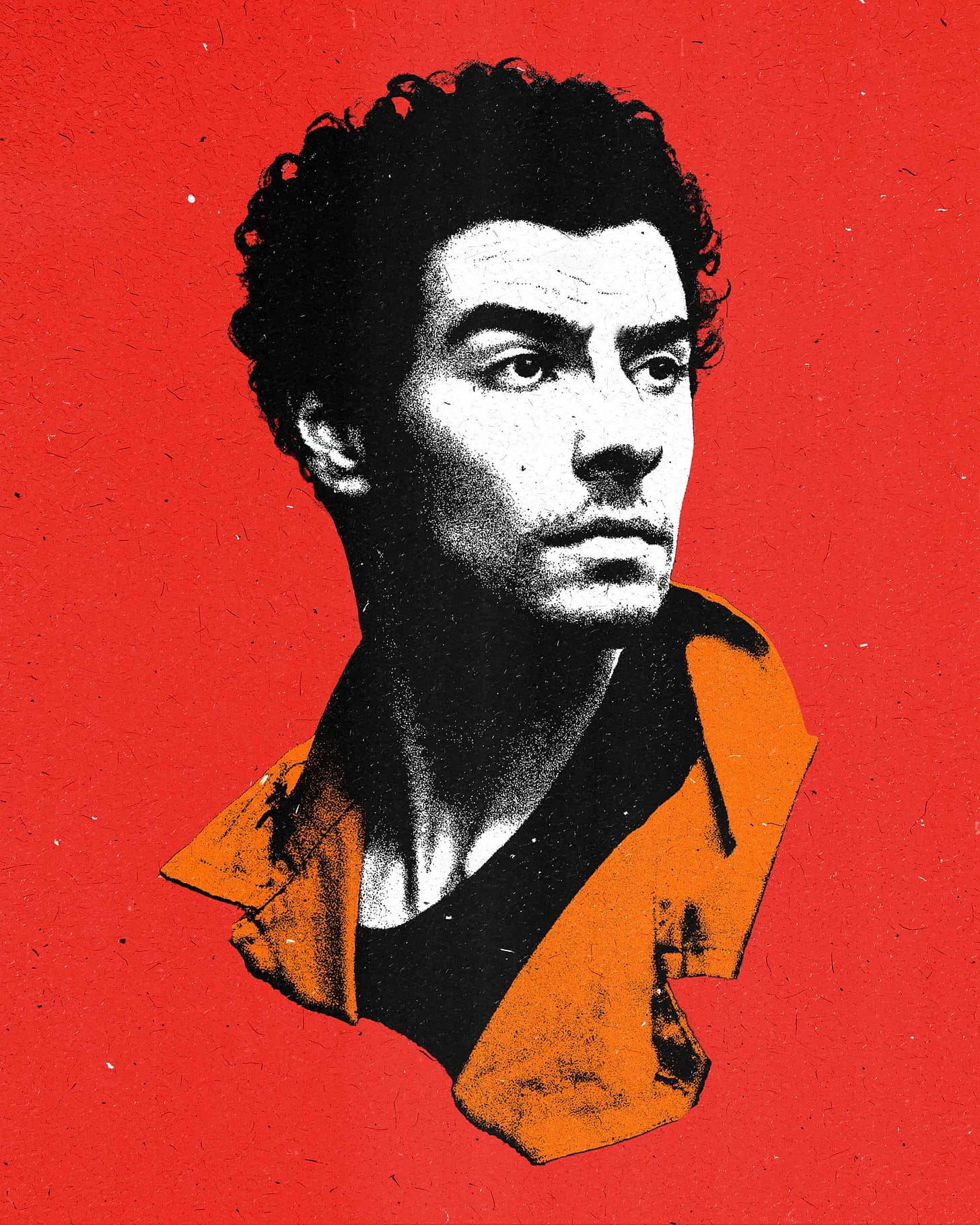

I give my preliminary thoughts on the Luigi Mangione case and respond to a viral article that's been going around critiquing Luigi's actions.

‘It’s No One’s Fault’

The article writes:

“You can’t kill your way out of a problem that’s ultimately no one’s fault.”

These systemic problems grow and persist precisely because they are treated as no one’s fault. Assigning blame to “self-propagating systems” allows every C-suite executive, like Thompson, to abdicate moral responsibility. While Thompson ‘merely operated’ within the system, he was a great beneficiary and enforcer of its logic. By targeting him, Luigi shattered the complacency that allows such systems to thrive unchecked.

Luigi forced a conversation that polite society avoids at all costs. His act was a mirror held up to a world that incurs limitless debt for military ventures but insists on cost-cutting and profitability when it comes to administering healthcare.

This is the deeper indictment that the article sidesteps entirely:

There is something profoundly sadistic and unholy about a system that commodifies life itself, converting the alleviation of suffering into a business model where care is rationed based on actuarial tables, quarterly earnings and shareholder value.

To the average person struggling to access care, the distinction between calculated cost-saving measures and outright neglect is academic; the outcome is the same: lives are lost, hope is extinguished and dignity is sacrificed.

The author’s sober explanation of economic constraints explains how the system operates, but utterly fails to grapple with what it means to live under such a system, to endure its daily humiliations. Luigi’s rage speaks to a universal truth: the commodification of health and survival is an affront to our shared humanity.

Writer Junot Díaz puts it bluntly and brilliantly:

“Who is surprised that a society held hostage by monstrous neoliberal capitalism and conditioned by its social sadism would in turn produce monstrous and socially sadistic reactions?… Folks would be less likely to cheer murder if they belonged to a society that didn’t itself murder so freely, so abundantly, so endlessly under the guise of ‘good business’.”

Helplessness and Rage

The article highlights Luigi’s concern with individual freedom and agency — Luigi felt that most people are becoming NPCs, unable to think for themselves — but the article fails to connect his concern to the colossal legal, financial and bureaucratic barriers that render individual agency hopeless.

Corporations like UnitedHealthcare operate within a fortress of legal protections, wielding armies of attorneys, lobbying groups, and regulatory loopholes to shield themselves from scrutiny. Channels for accountability are not just constrained, they’re often outright inaccessible to those without significant resources.

When corporations lobby to suppress reform that would help their patients, their resistance is disguised in procedural neutrality. Their genius lies in the ability to obfuscate this structural violence, framing it as the natural order of things. The machinery of profit-driven healthcare does not require individual malice to perpetuate harm — only compliance with its incentives and metrics.

Against this backdrop, Luigi’s alleged assassination — horrifying as it is in isolation — becomes intelligible as a desperate assertion of agency in a system designed to neutralize it. In such an environment, the moral calculus shifts: what options remain for those who lack wealth, power, or institutional support? The answer, for many, is despair — despair that, over time, metastasizes into rage.

Dehumanized at Every Level

The premature death of a father and husband is an undeniable tragedy — a pain no family should endure. But in a cruel irony, the same logic of ‘bureaucratic indifference’ circled back to Thompson himself.

Thompson was just a symbol, a scapegoat. It could have been any CEO. Thompson’s tragedy lies not only in his death but in his substitutability. Thompson’s name, face, and decisions were immaterial; any other CEO could have occupied the same seat. His role was as interchangeable as the millions of patients reduced to case numbers, actuarial risks and bottom-line variables. A mother denied chemotherapy, a child’s lifesaving surgery postponed, an elderly man bankrupted by medical bills — all are liabilities to be minimized, expenses to be managed, costs to be contained.

The system erases humanity at both ends: in the patients whose suffering is abstracted into numbers, and in the executives whose decisions are dictated by spreadsheets and shareholder demands.

A legalized killer is called a soldier; the only difference is who decides which violence is 'righteous' and which is 'inhumane.' Luigi's actions, while undeniably polarizing, raise critical points about the systemic violence inherent in modern society—wars fought under the guise of righteousness, the dehumanization of individuals within profit-driven systems, and the way history whitewashes atrocities. Every revolution has its martyrs, those who force society to confront uncomfortable truths at great personal cost.

While I don’t condone murder, it’s impossible to ignore that systems built on exploitation often create conditions where extreme actions become symbols of resistance. Luigi’s actions have sparked a moment of reckoning, challenging the complacency of a world that profits from reducing human lives to statistics. Perhaps the greatest tragedy is not the individual casualties but the normalization of systemic harm that brought us here.

Such a great rebuttal to Gurwinder’s take. Really well written, thank you for this.